I’ve been reading science fiction and fantasy almost as long as I’ve been able to read, and I’m normally very good at suspending my disbelief. Unfortunately, seven years of university schooling and two degrees have now placed some suspension limits on certain areas—namely geology, landforms, and maps. I tend to notice little things like mountain ranges having ninety degree corners or rivers that flow uphill or maps that don’t have a scale bar.

So I want to talk about some things, which on-a-geological-scale are very small details that make me tilt my head like a dog hearing a high-pitched noise. Not because I hate, but because there is no more honorable nerd past-time than dismantling something we love into its finest details, ruminating endlessly on the bark of a single tree while there’s an entire forest planet surrounding us.

Which is what I’d like to talk about today, incidentally. Single-environment planets. The other stuff, including scale bars, will come later.

I like desert planets, and it’s the combined fault of Dune and a semester of examining lithified sand dunes that are now absolutely gorgeous rock formations.

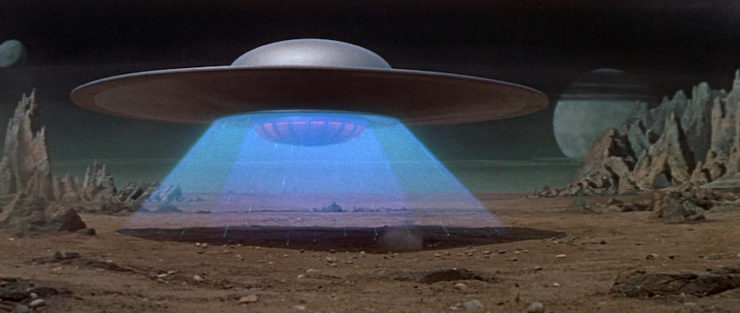

Arrakis wasn’t the first desert planet of science fiction—at the very least, Altair IV as seen in Forbidden Planet has it beat, and I’m sure there’s some pulpy goodness even earlier that involves desert planet adventures. But Arrakis and its direct descendant Tatooine are definitely the most iconic desert worlds of our genre.

As a geologist, I have a particular love of the desert and its landforms, ones that are normally more shaped by wind than water. (The descriptor for those is eolian, which is a particularly lovely word to say.) I did a lot of undergraduate field study out in Moab, and I grew up in Colorado, which has a lot of near-desert and desert environments. The dry hot-and-cold of the desert shapes you, in ways beyond an appreciation for chapstick and a healthy respect for static electricity.

There’s an inherent magic to the desert, whether you’ve ever been in one or not, a grown-in mysticism that comes with the unfamiliar. It’s a landscape that’s entirely alien to most of us, unimaginable for its lack of water, its alternating burning and freezing temperatures, its weird or absent plant life. The horizon in a desert extends on forever, because there’s no humidity to get in the way of your vision. The only real limit is the curvature of the planet, elevated land features, or particulates in the air. Even the sunsets look different, if you haven’t lived your entire life where it’s incredibly dry. (Let me tell you, the first sunset I saw in a place with humidity actually scared me because it looked so different, with the Sun hovering massive on the horizon like a blood-filled Eye of Sauron.)

There’s a quiet to the desert that sinks in through your skin, a hush that’s only the sound of the wind. Rodents or insects moving around sand grains or pebbles sounds shockingly loud. Birds startle you. And the sky at night? You’ve never seen so many stars in your life, if you’ve never been to the desert. Being out in the middle of nowhere cuts out all the urban light pollution, but beyond that, there’s few clouds, no humidity to blur and hide the sky.

Of course, there’s this common conception that deserts are like very specific portions of the Sahara, with undulating dune seas that go to the horizon. Arrakis and Tatooine both have a lot to answer for on that front, but I will admit that barchanoid (crescent) and transverse (linear, if wavy) dunes are particularly photogenic. And while those are what capture the imagination, both Dune and Star Wars admit there’s more to their desert worlds than just endless draas. Arrakis has extensive salt flats (sometimes called “saltpan” colloquially in America) that are the skeletons of extinct oceans and lakes. There are rocks and mesas that poke their heads above the sand. In Star Wars: Episode IV, we get a brief look at Sluuce Canyon—which might also mean there was once a fast-moving river there, or it could be a tectonic artifact. But either way, it’s a change from the dunes.

And let me tell you, there are a lot more landforms in the desert beyond those. There’s hardpan (basically rock-hard clay surfacing) and desert pavements of packed stone, with or without desert varnish. There are deflation hollows (where sand has been blown away from rock outcrops, leaving a hollow), dry steppes, and an assortment of strange rock forms shaped by wind and blown sand (yardangs). For all its many faults, Star Wars: Episode I got one thing right—we get to see a scene during the pod races with a hardpan plain riddled with mud cracks and darted with wind-shaped yardangs.

Deserts can be as hot as you imagine or impossibly cold. This is because the factor that determines if something is a desert is precipitation. That’s it—everything comes down to how much water falls from the sky. Latitude doesn’t matter, sand or lack thereof doesn’t matter, just that it’s really, really, really dry.

This is why as a geologist, I don’t have to suspend my disbelief very far to journey to a world that’s all desert. I’d like to see more than just sand dunes, but I can tell myself that for some reason, all the people want to just hang out in the sand and ignore the other areas. They’re believable—they even exist in our very own solar system. Just look at Mars! (Mars is a desert whether it has water hiding under its surface or not; what matters in this case is that it certainly hasn’t rained there in recent geological time.) If you look through many pictures of the red planet, you see all that variation in local land forms I mentioned, from classic sandy dune seas, to dry mountains, to empty canyons, to rocky landscapes of what might be equivalent to pavements. All you need to get an entire planet that’s a desert is reverse that ubiquitous direction for ready-made products—just remove the water. Voilà, instant desert!

Then, of course, you have to address how the hell anyone actually survives on that world, but that’s your problem. I just deal in rocks.

Mono-environment invented planets don’t work for much else, though, with the possible exception of the ice ball world. (Even then, depending on your land masses, there might be more than just glaciers out there. But I’ll give the benefit of the doubt on that one.) The real issue is that worlds are spherical-ish (“oblate spheroids,” if you’re nasty), and they tend to get their input of light and heat via orbiting a star. The unforgiving realities of geometry—sphere versus what is effectively a uni-directional point source—dictate that the distribution of heat is never going to be even, which means you’re going to get atmospheric currents, and those mean that the distribution of precipitation is never going to be even, and as soon as you add that plus your unevenly distributed landscape and unevenly distributed bodies of water, you have environmental trouble. If your entire world is so hot that there are tropical rain forests at the poles, what the heck is happening at the equators? How is your rainfall and temperature being so regulated that there’s jungle everywhere? Have you never heard of mountain rain shadow effects?

This is why, once we leave Tatooine, the world-building in the Star Wars universe generally loses me. Having an entire planet that’s made up of rainforest-covered archipelagos as far as the eye can see looks very pretty on the screen with a starship zooming in, but it awakens a lot of deep and worrying questions in me, including (but not limited to) just what is happening with the plate tectonics?

Please don’t think I want a deep, loving, exhaustive description of how the plate tectonics on your planet work. I don’t, and I say this as a geologist—I’m sure no one else does, either. But there needs to be a reason, a level of believability, and if it ain’t a desert, it ain’t going to work. And remember even then, you’re still not going to have an Arrakis that is one massive dune sea that’s all the same temperature. The landscape varies, and that variation provides a certain amount of character and realism—it’s a similar principle to when directors in movies want sets to look “lived in.” The variation in landscape makes the planet alive, even in a world that seems as sterile and dead as one giant desert—because trust me, deserts are neither sterile, nor dead.

They never stop moving, as long as the wind blows.

An earlier version of this article was originally published in May 2017.

This was a great article!

It also makes me wonder about the planet Vulcan. Is such a life-sustaining world ecologically possible?

While Vulcan is drier and hotter than Earth, shots of it from orbit have shown that it does have a number of small bodies of water and polar ice caps. Voyager established the names of two bodies of water on Vulcan, the Voroth Sea and Lake Yuron. Discovery even showed rainfall in a scene at Sarek’s home. So it’s not a single-biome planet like in Star Wars.

I also love the desert in its many forms, although I only know the desert southwest US. But the one thing that I don’t understand about Arrakis ecology is how the sandworms get so big? Most indigenous life there seems pretty small. What did the sand worms eat before the spice harvesters showed up?

Sandworm ecology? All handwavium. Leaving aside biomechanics of this huge creature, how does this planet maintain an environment habitable for humans?

John Varley made the point that a burrower of that size would have a great deal of difficulty overcoming the friction its great surface area would generate as it tried to eel its way through the sand.

Good article. Though I thought in the original Dune it was stated that the known settlements are pretty much just in the northern polar region, and that it was assumed that everywhere south of the polar circle was just too hot to sustain non-shaihuludian life. It turns out that was not quite the case and that the Fremen had many hidden settlements in the south, but still, it was pretty damn hot elsewhere.

Listen, I love Rogue One with every fiber of my being, and what I know about earth sciences you can conceal inside R2D2. But I refuse to believe that there’s nothing on Eadu but jagged peaks and endless downpours.

>>If your entire world is so hot that there are tropical rain forests at the poles, what the heck is happening at the equators?

So… *is* that a geologically viable set up? Jungle poles, uninhabitable hellscape equator? Because that sounds like a pretty cool setting in and of itself.

Ooh! What if they used to have technology that let them pass through the Hell Zone, but something something collapse of civilization something, and you end up with two completely separated human populations, one at the north pole and one at the south pole? I’m seeing some great plot/worldbuilding potential here.

You want a fun world, read “Uller Uprising” by Piper. The planet is tilted 90 degrees to the ecliptic…

Pournelle and Niven had a prison planet, Tanis, I think, which was tropical at the higher latitudes and so hot at the equator that the seas boiled.

They don’t seem to have thought of what this would do to the planet’s hydrological cycle, and “runaway greenhouse effect” also never came up.

Since neither Niven nor Pournelle seem to believe in climate science (see Fallen Angels), it’s unlikely they’d think of it. In their defense, “hard” sf has science negligibly better than that of high fantasy.

I once had an idea for a hot planet uninhabitable in the tropics, so that entirely separate biospheres and intelligent species had evolved in the north and south polar regions, and eventually they crossed the vast desert in between and made first contact. I’m not sure now if that would really be plausible. A planet would probably be unlikely to maintain a constant temperature for the whole time necessary for a biosphere to evolve. There might have been times in the past where it was cooler and species exchange happened between north and south. But there could still be story potential if the civilizations evolved entirely independently.

That sounds very plausible if you’re a penguin.

“But Arrakis and its direct descendant Tatooine are definitely the most iconic desert worlds of our genre.”

What, no love for Barsoom? How quickly we’ve forgotten.

“How is your rainfall and temperature being so regulated that there’s jungle everywhere?”

There are lots of different sorts of jungle. You don’t have to have tropical heat to have a rainforest – there are montane and temperate rainforests – and “jungle” is just another word for “dense unmanaged vegetation”, which doesn’t need particularly high levels of rainfall (though it does need some). Most of Europe was jungle not too long ago. Practically everywhere where people can live a civilised life – ie more than just a sparse population of nomad herders or hunter-gatherers – has enough rainfall to revert to what could loosely be called jungle.

And at least on an all-jungle world you don’t have to answer the question “where are you getting your oxygen from”?

“healthy respect for static electricity.”

I lived in Cedar City Utah for 10 years and I had a good ground next to my computer so I could discharge myself before I touched the keyboard. It doesn’t take much to turn a silicon chip into a circuit with infinite resistance.

Doesn’t a climate with subtropical poles, lower equator to pole temperature difference and low seasonality describe the Late Cretaceous and Mid-Eocene warm periods? Polar sea-surface temperatures were in the 20-24c range tropical SSTs in the 28-44 range. It was hot, probably too hot for humans, but there was still a lot of life at the equator.

The oceans were much more extensive in those periods, and that may have ameliorated low-latitude climates to some extent.

Well there had to be some reason we call STAR WARS ‘Space Opera’ more often than Science Fiction! (-;

George Lucas has never claimed Star Wars to be science fiction. There’s never been a shred of science in it. His term for it is “space fantasy.” It’s in the “sword-and-planet” genre of things like Flash Gordon and John Carter of Mars, sword-and-sorcery tales in a fanciful outer-space setting.

Fwiw Arrakis is not barren / completely desert due to any geological phenomenon, but because of the sandworms.